The Butterfly Nebula is one of those cosmic objects that demands our attention, and even our fascination. It’s also known as NGC 6302 or the Bug Nebula, but whatever name we use, the stunning spectacle of ionized gases draws our human eyes in. In fact, Butterfly and its nebulae brethren may be more responsible for generating public enthusiasm in astronomy than any other type of object.

The Gemini South Observatory is an 8.1 meter optical/infrared telescope high in the Chilean Andes. It has a sister telescope in Hawaii called the Gemini North Observatory. Gemini South is celebrating 25 years of service, and as part of those celebrations, the National Science Foundation, which operates Gemini, ran an image contest. It’s called the Gemini First Light Anniversary Image Contest, and the contest reached out to students in Chile to select a target for Gemini South to celebrate its 25th anniversary. (Gemini North celebrated its 25 years back in June 2024.)

In a poll, the students had to choose either a star-forming nebula, a supernova remnant, a star cluster, a planetary nebula, or a galaxy. They chose the Butterfly Nebula, which is a planetary nebula. As most astronomy-minded people know, planetary nebulae have nothing to do with planets. It just appeared that way to early astronomers, and the name stuck.

This zoomed-in image shows the blazing light in the center of the Butterfly Nebula. Image Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA. Image Processing: J. Miller & M. Rodriguez (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab), T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab), M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab)

The Butterfly is about 3,000 light-years away in the constellation Scorpius. It’s classified as a bipolar planetary nebula, because two lobes of gas have spread out in opposite directions from the white dwarf at the center. This feature makes it almost instantly recognizable.

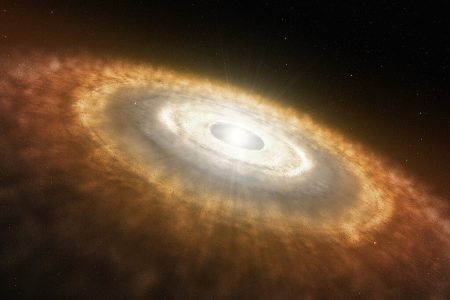

The progenitor star was formerly a main sequence star that aged and evolved into a red giant. As a giant, it ceased fusing hydrogen and went on to fuse successively heavier elements. Eventually, it lost so much mass that it became bloated and unstable. Its powerful stellar winds blew much of its gas away, which formed the nebula.

The white dwarf is the stellar remnant of the precursor star, and it’s actually one of the hottest stars we know of. Its surface temperature of about 250,000 Celsius (450,000 F) indicates that its progenitor was quite massive. The star is much less massive now that it’s shed much of its gas. It’s buried at the center of the nebula, and was only recently identified by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009. Butterfly is classified as an emission nebula because UV light emitted from the extremely hot white dwarf ionizes the expelled gases, lighting them up and creating this gorgeous display.

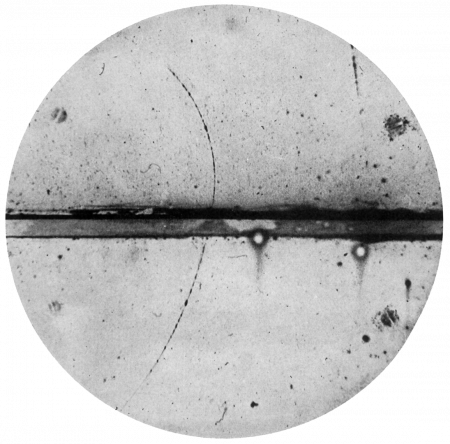

*The Hubble captured this image of the Butterfly Nebula in 2009, after a servicing mission installed the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). The reddish outer regions indicate ionized nitrogen, while the white regions indicate ionized sulphur. Image Credit: By NASA, ESA and the Hubble SM4 ERO Team – http://www.hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2009/25/image/f/, Public Domain*

*The Hubble captured this image of the Butterfly Nebula in 2009, after a servicing mission installed the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). The reddish outer regions indicate ionized nitrogen, while the white regions indicate ionized sulphur. Image Credit: By NASA, ESA and the Hubble SM4 ERO Team – http://www.hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2009/25/image/f/, Public Domain*

The progenitor star cast off its outer layers about 2,000 years ago, when it was a red giant with a diameter about 1,000 times greater than the Sun. Those outer layers moved slowly and form the dark, doughnut shaped band that’s still visible in the image’s center. The star expelled other gas in a perpendicular direction from the band, forming the pair of lobes, or the Butterfly’s wings. But the fun didn’t stop there.

As the giant star suffered its death throes, it expelled a gust of powerful stellar wind that ripped through the lobes at extremely high velocity, more than three million kilometers per hour (1.8 million miles per hour). As this fast gust reached and interacted with the previous slower winds, they formed an intricately detailed structure of clumps, filaments, and voids, all made of gas that was once part of the star.

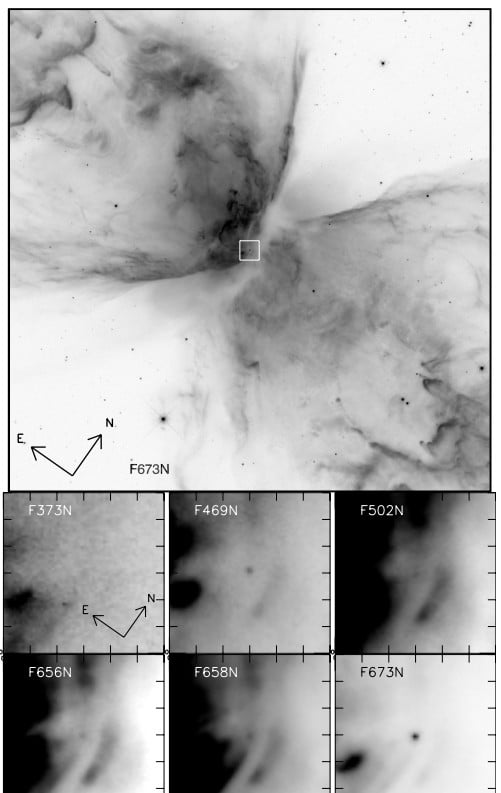

*The images from the Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 were the first to identify the central white dwarf star in the Butterfly Nebula. Image Credit: Szyszka et al. 2009. ApJ*

*The images from the Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 were the first to identify the central white dwarf star in the Butterfly Nebula. Image Credit: Szyszka et al. 2009. ApJ*

The images of the Butterfly Nebula from Gemini South and the Hubble are calibrated differently. In the Gemini image, the rich red colour represents ionized hydrogen, while the blue regions indicate oxygen. In the Hubble image, red indicates nitrogen and white indicates sulphur. Regardless of what colour is assigned to them, the hydrogen, oxygen, sulphur, nitrogen, iron, and other elements in the nebula will go on to form the next generation of planets and stars as the Universe continues its cosmic recycling mission.

Stunning images like this were out of reach for our ancestors. They had no idea that anything like this existed, or that stars evolved and changed over time. They had no way of seeing or knowing any of this.

But we moderns do know this, or at least educated and/or curious people do. Beyond its beauty and its fascinating form, the Butterfly Nebula shows us that nothing lasts forever and everything is always changing. Each star has a limited lifetime, even if its measured in billions, even trillions of years. That means each planet only lasts a certain amount of time, and by extension each eon, each period, each epoch, and each age are also limited. That means that each civilization, each species, and each biosphere also exists for a limited period of time.

So do each of our lives. Eventually, the Sun will expand into a red giant, perhaps consuming the Earth. Earth itself will be destroyed, and all of the matter that made up every human that ever lived will be spread out into space and taken up in the next generation of star and planet formation. There is no forever.

We’re fortunate because we have the 25-year-old Gemini South Telescope, and other telescopes like the Hubble and the JWST, to enrich our lives with this cosmic context. Groove on the meaning of it all.

Listen to the full episode here